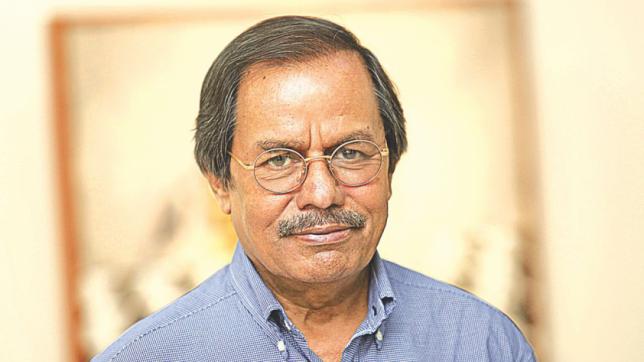

This is an Interview with Prof. Syed Manzoorul Islam which was covered by Altaf Shahnewaz and published in Prothom Alo on 26 October 2018. What follows is a translation of that interview:

By Fairuz Maliha Surma

Sir, your first book Nondontotto was published in 1986. What’s the story behind it?

– I write for my own pleasure, I don’t write with the purpose of publishing it. Before publishing the book, I wrote a few articles, also a story, which was published in 1973 in the newspaper Bichitra, and was named “Bishal Mrittu.” Before that I worked on a couple of write-ups regarding painting. As I started to write the book, though, I thought that I needed to take a lot of preparations for it. After all, you know how a book keeps on roaming from hand to hand. If any reader finds out any weakness, how would I feel as a new writer? For this, I was not being interested to publish the book. Besides, the publication environment at that time was limited. Even a great number of famous writers had to run after publishers to publish their books. Banglabazar was the center for publications. I didn’t go to Banglabazar as I was not interested in publishing the book. When Bangla Academy showed interest and I was told that I could write for the martyrs in the book fair, that’s when I started to write Nondontotto. And this is how my first book got published.

In 1973 your writing was published in the famous newspaper Bichitra. Then again you began to write stories in the late 90’s. What is the reason behind such a long break?

– After Bichitra published my work I was both appreciated and criticized. I felt that I needed more preparation. On the other side, I started teaching in 1974. Before every class I had to study for 3 to 4 hours for my own self. There were even elder students than me in the MA preliminary class. If I was not well-prepared, what they would feel was also a matter of great concern. Then I went to Canada for my PhD, and came back to Bangladesh in 1981. Maybe for all these reasons, the break was longer than I wanted it to be. But going to Canada actually helped me a lot. I got to know about the Latin American literature from our university’s huge library. I even took a course on that. After completing the course, I came to know about the effects of oral literature both on classic and contemporary written literature, modernization and also the strong presence of historicity in art.

Most of our writers’ first attempt at creative writing starts with poems. Is it the same with you, too? Do you remember the earlier days of you writing?

Ans- Any educated Bangalee’s literature practice always starts with poems. It is not that I didn’t write poems as well, but I wrote them mostly because some friends of mine inspired me. I didn’t have any ambition regarding poems. And if I want to talk about my first days of creative writing, then I need to say that I started writing stories because my father wanted so. In 1961 my father was in the Teacher Training Center in Mymensingh, and over there, a magazine used to be published named Shikkhok Shomachar. He wrote me a letter asking me to give my writing for that magazine in the section preserved for teenagers. I had to write according to my father’s wish. We had few magazines about children and teenagers in our home. I used to read them with great pleasure, which is why I felt no issues during my writings. I submitted yet another one for a different magazine named Rongdhonu. After entering college, I sent some fictional pieces to Mahe Nou Potrika. At that time writers like Borhan Uddin Khan Jahangir, Alauddin Al Azad, Abul Hossain, and so on also used to write for that paper. I had two of my writings published in that newspaper. They used to give me 15tk per writing at that time.

Your writing style is slightly different from the other contemporary writers of Bangladesh. Your writings are somewhat next to colloquy. No ornate expressions are involved. What do you have to say on this?

– If you say like this, I’ll feel that I’m neglecting our native history of writing literature. It is actually never like that. Keeping my full respect on that tradition, I’m trying to find a new angle, the angle which is actually not new but have been there since a thousand years. And that is our own style of storytelling, oral expressions, and the way we talk in tradition while adding ‘the new’ to it at the same time. I felt there are more scopes for comfort, elasticity, self-reflection, and creating proximity with readers as one tells the story and the audience listens to it. Our tradition of writing owes to the West and follows the modernity of theirs. Freudian psychoanalysis and western/urban rationality reveal newer doors to our understanding of the deeper complexities of a protagonist’s psyche. On the other hand, it also involved a mindless absorption of non-native topics and styles. Suddenly, it seemed the mode of expression was abstract, the language was complex, and the very content itself was incomprehensible. So, one thing to ask here is did we share the same socio-cultural context, academic interpretations, methodologies and logic with the West? No. The phase was seen after the WW1 in this terrain, but I do not think it is fully reflected in our reality right now. We are a bit of emotional in our daily life, we do not always care about logic. Then on what expression of modernity are we working? I think that we have created a Bangladeshi or West Bengal version of Western modernity. If you ask me whether it is good or bad, that is totally a different matter of consideration. Many have shown their autonomy incorporating the non-native context. They are meritorious. But if the living reality of this particular South-Asian context is given a serious thought, as in how the Western ‘coat’ has covered the local, perhaps a sense of a double-face does emerge somewhere in between.

What do you mean by this retention?

– The gap which remains (and will do so) between the Western traditional modern thinking and our traditional reality is what I meant. When we encounter life as it is, we can probably come across a Prufrock or Stephen Dedalaus within ourselves, but when we write in the manner of a writer then there is a good possibility of using a language that is not close to your heart. At one time we showed a writerly tendency to write in the weighty Sanskrit, filled with totshomo and tadbhavo utterances. Now we have moved on it seems, luckily. After 1947, Bangla had to change, almost mandatorily. We have distanced ourselves from West Bengal. It is obviously a positive thing. Still there are some young emerging writers, in whom I do not see the willingness to seek mastery in their own language. As a result, what is happening is that, what most of us are trying to say being as authentic as possible, are gradually losing their uniqueness before reaching the readers. The patterns of complexities that have been produced in us for a long time or in the study of modernity have begun to settle within us, slowly yet effectively. If we want to be rescued from this situation, we have to come out of the Western modernity.

From the very beginning I’ve been thinking how the beautiful unknown pearls that are hidden in our oral tradition can be used to write, or should I say, tell a story. I took a decision that I’ll find a way somehow. That way has come to me through storytelling. I’ve grown up with it. I’ve listened to hundreds and thousands of them in puthi versions during my childhood. A beautiful combination of written and also, oral qualities at the same time, it is one of the best examples of how Bangla literature works. I was searching for this spontaneity of expressions, and found it quite easily in stories and narratives. I can repeat the same thing in three ways, and whatever I’m trying to say, although it has been already said in the vast realm of literature multiple times, it is acceptable and it becomes acceptable in all measurement. If I forget the name of some character, no one is going to scold me. When I’m saying the story from a place of the narrator, I’m gaining a sense of freedom within myself. I think that we did not properly investigate our tradition, which is why we are yet to achieve excellence in understanding and thereby, writing our own stories, undisturbed and focused.

You are saying that while producing a modern piece of writing, there stays a danger of writing what one didn’t really mean to write. But when you bring the oral within the written, is there no chance of the same to happen?

– Excellent question. The answer is, obviously, there is. The idea of writerly integrity lacks when we talk about the literary tradition as an irreversible constant, and we write only on its terms. It is to be remembered that, firstly in that tradition itself there has been a lot of changes and enhancement, there has been a lot of changes in the mass mind and the mood of the time as well. It would be wrong to think that the storytellers are not modern. There might be questions about life that a village story teller may ask, and there is depth in them too. He researches according to his own style. Now if I want to judge my life according to the structure of that of the West, then it will not make sense. Again, I have some troubles as well. There is repetitiveness in my writing, there is exaggeration, the distance between the reader and the writer is often a matter which stands out. But I believe, these types of troubles help me find newer ways of thinking and elaborating them.

You have been observing the literature of Bangladesh for a long period of time as a writer, reader, critic and teacher. What will you say about the post-independence Bangladeshi literature?

– 1971 has changed us. It has given us some subjects which have made us look at things in a complete new way. We have found our own language, have written according to how we think, and have built a place which is unresisted. Here the contribution came from the talented writers from the ‘60s and ‘70s and also those who have debuted after that, amongst them a few are- Shahidul Zahir, Andalir Rashdi, Shahnaj Munni or Sadia Majzabeen Imam. (There could be more 20-22 names added in this list but according to the limited space, it cannot be written, therefore seeking forgiveness). And if I have to say about the tendency of writings nowadays, then I’ll say that there are many juveniles who are writing with an open mind. Also, there are some who are writing without taking enough preparation. As this last stage of modernity arrived, there were a lot of things to write about. But What I’m not finding in our literature is, subtle humor. Other than this we are yet to excel in literary criticism as well.

Why is there not enough literary criticism, you think?

– Literary criticism is only found in a territory where the people of that country are truly literate. It means that they can take the culture of education freely, open mindedly. They have books in their hands, in their homes. The readers are conscious; they can comparatively evaluate and analyze something. Are our readers like that? Hardworking critics are nowhere to be found, too. A critic like Abdul Mannan Sayed cannot be seen nowadays.

On a related note, you received your higher degrees from the West, but you have written stories and novels following your domestic heritage. What do you have to say on this?

– Long ago, the education system in South-Asia underwent the colonial power. We have been forced to receive education from the western countries. Our education, research, urban culture, justice system etc. are bounded within the same walls of the West. I have tried to come across this wall of boundary and the Bengali heritage has helped me. To be honest, I take from the West as much as I can, but I’m trying to maintain a balance. How much I’ve been successful that I do not know.

You have been writing for a long period of time. You have also achieved awards and honors other than Bangla Academy and Ekushey Padak. Any thoughts?

– I do not have any dissatisfaction. In fact, I have received more than I’ve given. Maybe this is because I’m a teacher.