Hollywood filmmaking has been dominated by postmodern cinema since the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting and influencing the historical fusion of media culture, technology, and consumerism. The post-Fordist, globalized era of capitalist development that it represents is characterized by growing class conflict, social atomization, urban turmoil and violence, ecological crises, and widespread depoliticization. Postmodern cinema is distinguished by disjointed narratives, a dark view of the human condition, images of chaos and random violence, the death of the hero, an emphasis on technique over content, and dystopian views of the future, departing from the modernist cultural tradition established on the Enlightenment, industrial society norms, and faith in historical progress. Although postmodern filmmakers like Woody Allen, Oliver Stone, Robert Altman, Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers, Mike Figgis, and John Waters frequently make films that are incredibly original and even subversive, their break from standard Hollywood formulas and motifs that define the studio system – their pronounced cultural radicalism – is rarely connected with any kind of political radicalism, even where a harsh social critique might be evident. The highly prevalent feelings of angst, uncertainty, fear, and cynicism that postmodern film tends to perpetuate are those that are present in society at large.

Postmodernism in film includes pastiche of many various genres and styles, technical self-reflexivity, and a breakdown between the high and low arts. Postmodern films are able to produce a distinct style of many various sorts of films into one seamless film by blending diverse components of many styles of cinema and genres. For this article I have cherry-picked two different films of Hollywood, directed by two renowned directors, who have shaped the very claylike idea of postmodernism through their visionary pieces of art.

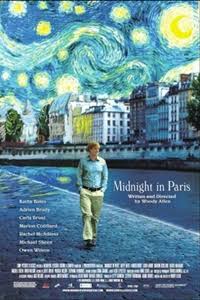

Midnight-in-Paris (2011)

Woody Allen is the kind of director who has developed his own cinematic languages. He does not believe in elevating form over content, but the convoluted narratives, and odd but brilliant plot techniques in his movies, make them distinctly postmodernist. Midnight in Paris (2011) unquestionably qualifies as his most postmodernist picture, after Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989). This movie examines two periods in French history, and travels back in recollection.

Magical realism is present throughout the movie. The film’s historical periods are simultaneously accurately described and fictitious in juxtaposition. There are allusions to the literary gods, artists, and performers from that time period. Allen creates a very lovely picture, but it also examines the sense of loss and dissatisfaction with the time period one is born into. One of postmodernism’s most prominent characteristics, nostalgia, has been covered in the movie. The character is forced to journey back in time, and at one point of the movie, even further back in an intriguing manner, thus, making it one of the most exquisite postmodernist movies.

Moonrise Kingdom

Wes Anderson’s films are recognizable as his own because of the fusion of high and low art. Anderson’s works demonstrate an intentional and self-aware adherence to postmodernism’s core characteristics, embracing both textual and meta-textual aspects of his self-made identity as a director. Pastiche is an important aspect of Anderson’s ‘style,’ comprising a large part of his characters, ideas, and narratives.

Moonrise Kingdom combines family drama, camp humour, and adventure into one film. There have been a few moments in the film where characters’ behaviours deviate from the genre’s conventional acts and appear implausible. One moment in particular is when Sam is struck by lightning and entirely swept away. He stands up, wipes his glasses off, and says, “I’m OK.” Another example is when Randy Ward summons the guts to leap twice across the rushing stream to save Commander Pierce from the flames. The narrator plays a compact role, where he can be seen as an information provider to other characters, who also create a bridge over an immediate knowledge gap created intentionally, by providing information in a slightly unexpected manner, before and after the chronological stream of the story. This is a postmodern aspect that differs from the traditional story.

The set is hyperrealistic, which gives the picture an unnatural feel. Anderson used a panning technique to offer viewers a dollhouse-like image of Suzy’s home, “Summer’s End”. Every room in the house appears to have been designed with precision and symmetry. This feature of postmodernism immediately gives the spectator the impression that this is a fictitious narrative set, in a make-believe world. Scout Master Randy Ward’s tent is another example of this. He has a picture framed nicely, a nice glass of drink, a bookshelf, and from the wall a painting is hanging down while accompanying a light, giving us a sense of not-a-mere-tent but a home. This is definitely not a usual tent arrangement, which serves to further undermine the audience’s conviction in the narrative and encourage them to consider it as a work of fiction.

The very concentration on underacting and overacting throughout the film refers to a certain metatheatrical quality that helps the film to be illustrated from a postmodernist point of view. The acting is monotonous and forced, highlighting the fact that this is a fictional plot in a film. Every conversation between Sam and Suzy, for example, is purposely mundane, but this is most noticeable in the flashback revealing their initial meeting. Such tone of characters which simply can be labelled as repetitive just gets transformed into a “soap-opera” like over acting along with the stream of the story, beginning when Captain Sharp declares “nobody is going anywhere”. This adds to the plot’s amusement, but it is also a point at which the audience disconnects and recalls they are watching a movie.

The film paradoxically challenges and reinforces preconceptions of race and femininity, while also criticizing and upholding normative notions of the nuclear family and youth. Suzy’s family in Summer’s End appears to be great from the outside since they are an affluent white family, living in a large mansion on an island. Suzy, on the other hand, is a social misfit, whose parents share a bed and whose mother is having an affair with Captain Sharp. The film also contradicts youth ideology by portraying the children’s characters, particularly Sam and Suzy as smarter or perhaps, more mature than the adults. When Sam expresses his affections for Suzy, Captain Sharp concedes that Sam is smarter than him, despite the fact that Sam is only twelve years old. Laura Bishop promotes gender stereotypes by scolding Suzy in the shower, claiming that she has been acting unreasonably because “women are more emotional.” Her mother objects to Sam’s bug earrings, reinforcing the idea that women are obliged to wear “beautiful things.” Finally, the film promotes racial stereotypes by depicting white, suburban Island life in the 1960s. The majority of the characters hold qualities found in any pre-assumptions about just any typical white family that can afford sending their children to summer camp.

Wes Anderson infuses postmodern themes in Moonrise Kingdom, making it both original and amusing. In this strange story, he also manages to ironically attack normative notions, while simultaneously reinforcing stereotypes to make the audience ponder. Wes Anderson has carved out a unique niche for himself in the contemporary film world. While Anderson is known for his aesthetic and shooting style, as well as his production design and the use of the theme of dysfunctional families and love, he must also be remembered for his uncanny ability to combine two seemingly disparate film movements into a single film while maintaining his signature style. Pastiche, irony, and self-reflexivity are all dealt with in Postmodernism, but in a darker, more cynical fashion. Postmodernism’s desire for simpler times and sense of nostalgia helps to produce such a distinct, relevant viewing experience for audiences that keeps them coming back.